|

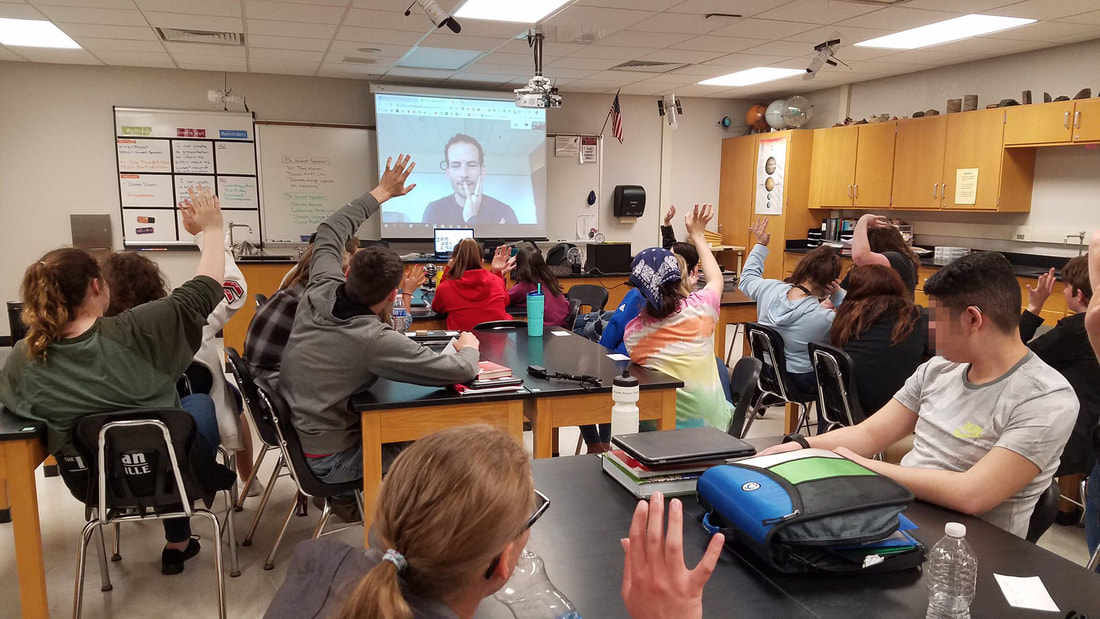

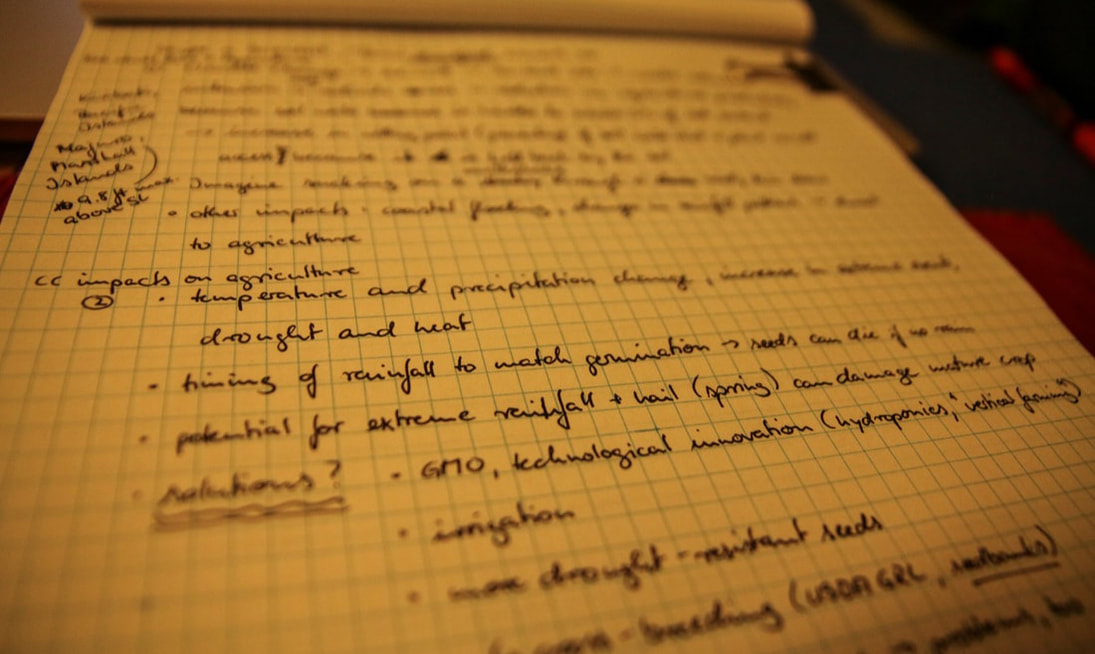

Two weeks ago, I received my favorite email newsletters: the biannual sign-up call for Skype A Scientist. If you don’t know, Skype A Scientist is an organization that matches researchers interested in science outreach with school classes to talk about their areas of work. Twice a year, in summer and winter, researchers sign up with their field of work, what grade levels they’d like to speak with (pre-school through high school and even adult and senior groups), what languages they feel comfortable with, and a few other criteria. Then, they are matched with teachers or groups who are looking for similar things. The organization sends both an email, and you do the rest to set up a video call The idea came from an emerging distrust and denial in science after Donald Trump won the presidential election in the U.S. in 2017, Sarah McAnulty, the Executive Director of Skype A Scientist, told me in a podcast interview. The organization is based in the U.S., but it operates globally. I started participating in 2018, and have talked to two to five school classes per semester, in English and German and mostly in the U.S., about climate change and its impacts on food production, grasslands, and natural ecosystems in general, about the water cycle, and about environmental topics in general. Preparation usually starts with an email from me to the teacher introducing myself, and the teacher emailing me more specifics about their interests, or with specific questions from their students. These questions are always fascinating to me. Over the next few weeks or months, until our scheduled session, I would look up resources, find photos, and put together some slides for the class. I always try to make it interactive, so I leave room for questions or include questions of my own that we then discuss during the session. I would often be on a huge screen or projector wall in classrooms, but during COVID when everyone was at home, I sometimes had Zoom calls with students in their PJs lounging on the couch (not that I’m complaining, I wasn’t exactly dressed for work either). It's important not to overthink answers, but to keep them short and simple. “How fast can wind go?” middle schoolers from a science class in California asked me two years ago. The younger the students, the more mind-boggling their questions. “Where is the cleanest water on earth?,” 3rd-graders from Switzerland wanted to know last spring. Younger students seemed to be more easily fascinated by our natural world, while older students would often have more specific questions. High schoolers from the U.S. East Coast asked me in 2018, “How much does climate change affect wildfires?” and “What do you consider to be the thing most impacted by climate change and why?” It's important not to overthink answers, but to keep them short and simple. High schoolers are also often interested in my career path, and how I got to where I am, since many of them will soon start college. After our sessions I usually share my slides and resources with the teacher, and include a list of additional resources — websites, literature, or online tools — that I like to share for their educational value. This semester, I was matched with two elementary classes in Florida and Louisiana. For me, Skype A Scientist is about more than restoring trust in science. As a climate scientist, it’s also a bit of therapy. It’s hard to describe the amazing feeling when students ask me what we can do about climate change. It is restoring my faith in humanity that we are not doomed yet (along with unplugging from ever more toxic social media, like Twitter/X). In addition, it is a way to humanize science, to show that scientists don’t all wear white lab coats and goggles and look down from an ivory tower. We are people like everyone else (the sign-up form also asks scientists — optionally — about race and gender, as a way to match minority classes with scientists from the same group). We don’t always have an answer (lots of times, no one does). But most of all, it is a way to get students interested in becoming scientists and channeling their natural curiosity for the betterment of the planet. Their questions are very important for me, because they tell me what will strike their curiosity, and I know that I won’t tell them something they already know or that is way beyond their comprehension. I can tailor our session to their needs and make it interactive. These questions often also neatly segue into broader topics. For example, the question about how fast wind can go, of course means talking about tornadoes in Oklahoma (cue amazing photos!), but I would also focus on what wind is, why we have storms, and why it is important (think pollination or rain in the desert). The question about the cleanest water, that was a way to bring up water pollution and what it does to our environment and ourselves. Sometimes I don’t know the “right” answer (What is the most important thing impacted by climate change?!), or I’ll have to preface it with a qualifier that my answer is based my own, limited expertise. Whenever I don’t have a good answer, I try my best and then ask the students back the same thing, just to see what they would say. Participating is free and on a voluntary basis for everyone. If you want to support Skype A Scientist, you can sign up as a scientist, teacher, or another group, or become a Patreon. Skype A Scientist: www.skypeascientist.com

Podcast interview with Sarah McAnulty (Executive Director): ECCN Podcast ep. 2 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed